Until recently, the idea sounded like something you’d hear in a late-night forum thread or see buried under layers of hype on social media. Two still photos. No video source. No motion capture. And yet, the end result looks like a short clip where two people move toward each other, adjust naturally, and kiss in a way that feels disturbingly believable.

It’s not magic, and it’s not romance either. What’s really on display here is how far facial animation and generative video systems have quietly advanced, mostly outside public attention.

The kiss is just the surface. The machinery underneath is where things get interesting.

How a still image stops being “still”

To a human eye, a photo is a frozen moment. To modern AI systems, it’s something closer to raw material.

Advanced facial analysis models scan an image and immediately start breaking it apart into structure. The shape of the mouth. The tension around the eyes. The way the jaw sits relative to the cheekbones. Even tiny asymmetries get flagged and logged. None of this is artistic interpretation. It’s pattern recognition built on enormous volumes of prior data.

Once that mapping is done, the image effectively becomes flexible. Not animated yet, but no longer locked in place either. The system now treats the face as something capable of movement, even though no such movement ever existed in reality.

This is where people often misunderstand what’s happening. The AI is not imagining emotions or intentions. It’s predicting motion based on statistical likelihood. What tends to happen to faces like this, under conditions like that?

Where the movement actually comes from

Motion generation is the hardest part, and also the least intuitive.

The system applies layers of synthetic movement derived from real-world video data: subtle head tilts, jaw shifts, lip deformation, and micro-adjustments in facial muscles. These movements aren’t copied from a single source. They’re averaged, blended, and reshaped from thousands of examples the model has already seen.

Timing is critical. Human perception is unforgiving when it comes to faces. If motion feels even slightly off, the illusion collapses. That’s why these systems intentionally introduce irregularities. Tiny hesitations. Minor imperfections. Things that would look like mistakes in traditional animation but feel natural to the human brain.

Ironically, realism often improves when things aren’t perfectly smooth.

Why one photo per person is enough

It feels wrong at first. Common sense says you’d need multiple angles or actual video footage. In practice, that’s rarely necessary.

The reason is aggressive inference.

When the AI doesn’t have visual data, it fills the gaps using probability. Side angles are estimated. Teeth are reconstructed. Hidden facial areas are guessed based on anatomical norms. Even complex movements are approximated from patterns the system has learned elsewhere.

What you’re seeing is not the person as they are, but a plausible version of them as they could be. That distinction matters.

It also explains why results can swing wildly in quality. Sometimes the output feels almost natural. Other times, something feels subtly wrong, even if you can’t immediately pinpoint why.

What actually affects how real it looks

There’s no single switch that controls realism. It’s the result of several variables interacting at once, some technical, some surprisingly ordinary.

The most important factors tend to be:

- Lighting and image clarity. Faces photographed in even lighting with minimal shadows give the system cleaner data to work with.

- Angle and facial visibility. Straight-on or slightly angled portraits are easier to animate than extreme profiles or partially hidden faces.

- Image resolution. Higher-resolution images allow finer facial details to be detected and animated more accurately.

- Intensity of the interaction. Subtle gestures are easier to render convincingly than complex or exaggerated movements.

- The underlying model itself. Different systems are trained on different datasets, which directly impacts motion quality.

None of these elements guarantees success on its own. Together, they determine whether the final result feels passable or uncanny.

The choreography behind the interaction

Despite how it looks, these videos are not dynamic interactions. There is no awareness, no response, no emotional exchange between the two faces.

What’s happening instead is choreography.

Each face follows a predefined motion sequence. Those sequences are aligned so that the movements intersect convincingly. The illusion of interaction comes from synchronization, not communication.

That’s why patterns repeat across different videos. You may notice similar head tilts, similar timing, similar mouth movements, even when the faces involved are completely different. The structure stays the same. Only the surface changes.

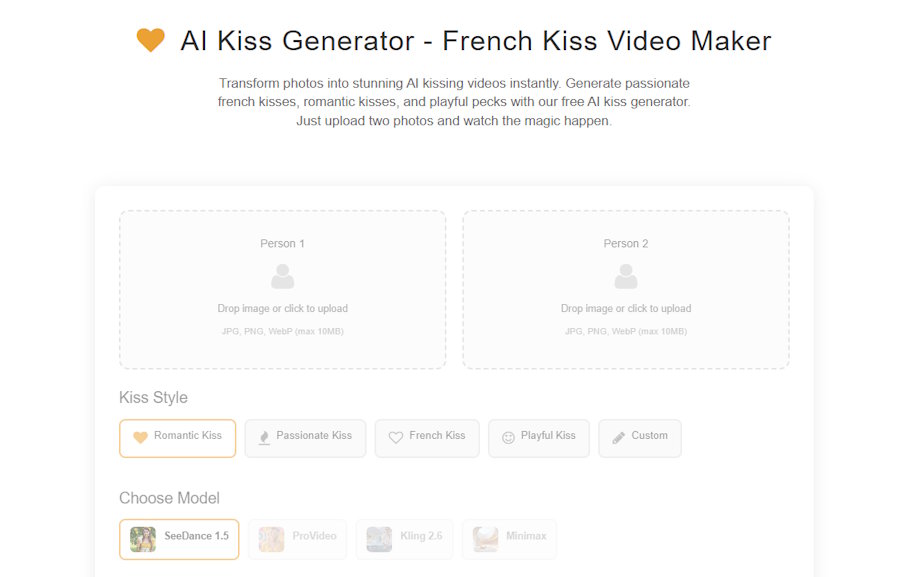

In discussions about this broader shift toward synthetic intimacy, writers sometimes reference tools like an online AI kiss generator as an example of how accessible this kind of animation has become, though the mechanics behind it are shared across many platforms.

How people are actually using it

Romantic curiosity is only part of the story.

A large portion of users approach this technology experimentally. They want to see what it can do. Others treat it as a creative tool, pushing boundaries simply to understand where those boundaries lie. And then there’s social media, where novelty tends to matter more than context or intent.

Short, emotionally charged videos spread quickly. They don’t require explanation. People react first and think later, which is exactly why this format performs so well online.

The ethical questions that won’t go away

The technical achievement is impressive. The implications are messy.

Animating real faces in intimate situations raises issues that can’t be solved by better algorithms alone. Consent becomes complicated when likeness is involved. The difference between playful experimentation and misuse is often subjective, but the impact on real people isn’t.

Common concerns keep resurfacing:

- Using someone’s image without their knowledge or permission,

- Blurring parody, fantasy, and impersonation,

- Emotional manipulation through fabricated intimacy,

- The growing difficulty of telling real video from synthetic output.

None of these problems is new. What’s changed is how easy it has become to create convincing results.

Why this feels more intense than other AI media

Fake text rarely shocks anyone anymore. AI-generated images barely raise eyebrows. Video is different.

Movement triggers emotional processing almost instantly. Eye contact suggests presence. Physical closeness activates deeply ingrained social responses. Even when you know something isn’t real, your brain reacts before logic catches up.

That reaction is what gives these videos their power. Not because they’re romantic, but because they tap into mechanisms humans evolved long before screens or algorithms existed.

Practical context for readers encountering this tech

For anyone trying to understand where this fits into the larger picture, a few grounded observations help keep things in perspective:

- The system imitates patterns; it doesn’t experience emotion.

- Input quality often matters more than technical sophistication.

- Ethical standards tend to trail behind new capabilities.

- The shock factor will fade, but the tools will remain.

What feels controversial now will eventually become familiar, and familiarity tends to dull outrage.

A subtle shift, not a dramatic one

Creating a kissing video from two photos isn’t a cultural revolution on its own. It’s a visible symptom of something quieter: the steady normalization of synthetic human presence.

The real story isn’t about romance or novelty. It’s about how little input is now required to generate something that feels emotionally real. A single image. A short wait. A result convincing enough to make people stop scrolling.

That pause, that moment of hesitation, is where this technology really lives.